Ama, Anak

Pro Gelladuga/ Renato Habulan/ Guerrero Habulan

March 10 to April 3, 2018

What is an identity? Is it a list of characteristics, visible or invisible, that can be rattled off as one would of the information in a birth certificate? Is it performative, something that has to be acted out continually, until something like habit emerges, shaping and defining the individual? Is it something that has been determined by genes and geography–a fact of body and place? Or is it the product of the intersection of biography and history?

In the three-man show, Ama, Anak, by Renato Habulan with his son Guerrero Habulan and son-in-law Pro Gelladuga, identity is the overarching theme in their works, a powerful signifier on how one conducts oneself in the world. It also announces to which groups we belong in—and excluded from. By contemplating identity through their works, the artists reveal what for them are significant markers and subject positions that exert the greatest influence on the individual and, by extension, to the collective.

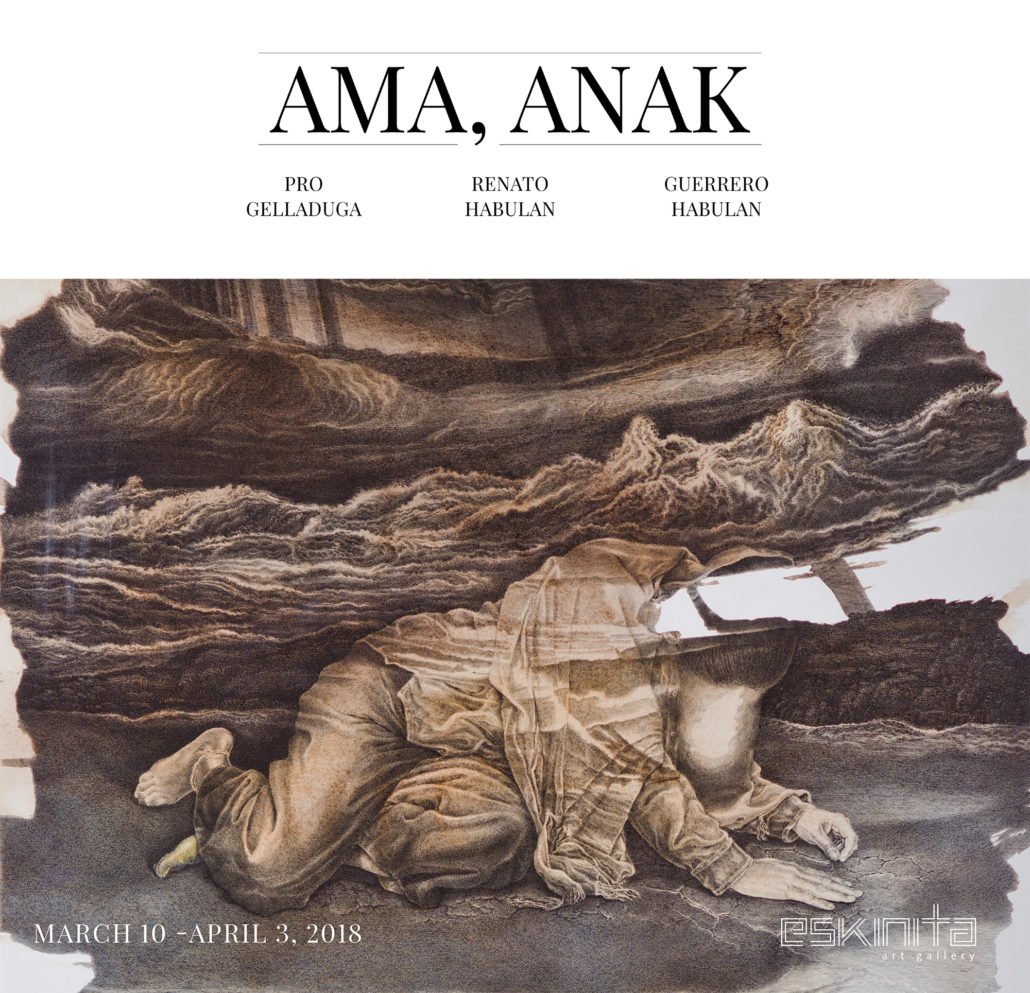

For the senior Habulan, a staunch Social Realist, identity is the confrontation between the local and the global, between the pre-colonial and the post-colonial, between the East and the West. In his monochromatic works of boseto (pen and ink drawings), we see the bulul ensconced on torsos wearing characteristic liturgical vestments. While the outside is affirmatively Catholic (religion, after all, was the cross that accompanied the sword in the subjugation of our country), the inside remains faithfully pre-Hispanic. The “primitive” is private. These two layers of identity nest onto each other in the single body (which can also be extended to society, the body politic) of a host, which has religious connotations as a symbol of Jesus Christ.

In one work, Jesus is shown as tied up, like a slave, against a field of felled branches, as an altar with Gothic spires shine from the distance. The juxtaposition is damning, as the feudal system brought here by the Spanish, has lashed much suffering at farmers and land tillers, the ordinary men and women that Jesus beseeched his followers to love and serve. As we spend resources in outward manifestations of piety, the least of brethren, as represented by Christ, are treated with indignity.

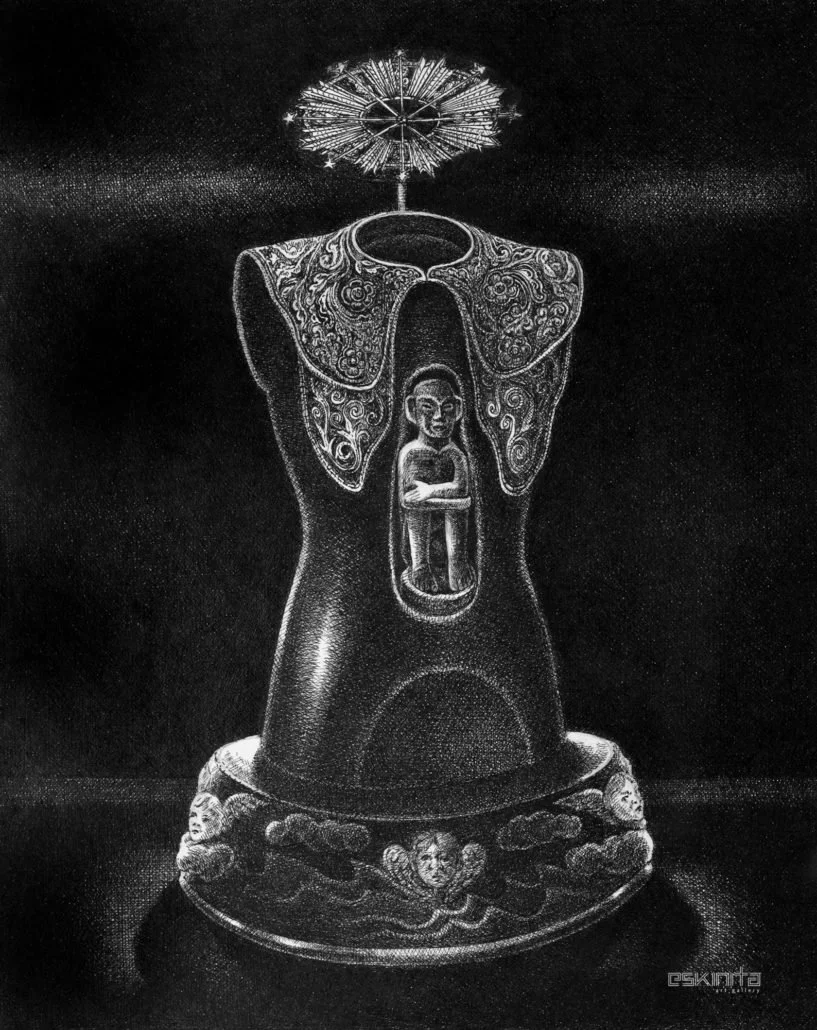

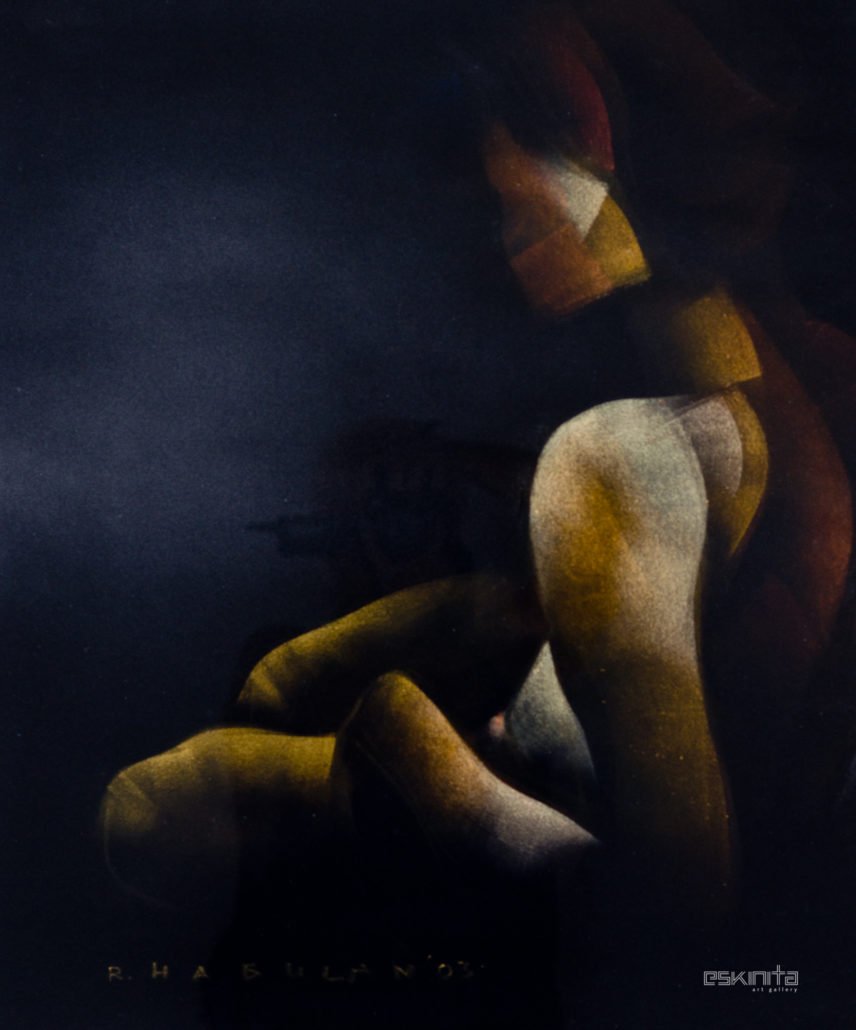

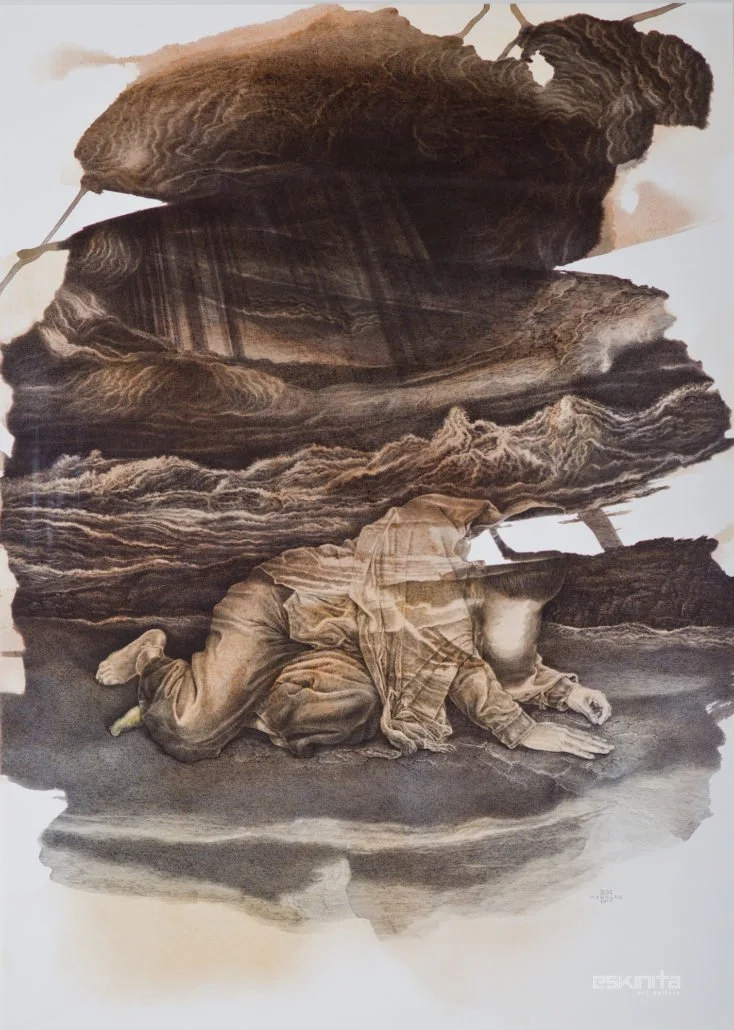

The young Habulan, on the other hand, contemplates on how other people, particularly those who have lived before us, continue to exert their influence in our day-to-day lives. The connection, certainly, may be traced to DNA, but the artist is also interested to see the transference of ideas and technology, how the present is but an accumulation of previous failures and achievements. These are visually translated as splotches, textures, and abstract forms that serve as a background to his figures of modernity, all the while carrying the burden of history—the incongruous heads on top of theirs.

In Gelladuga’s works, identity is centered on the phenomenon called the “third culture kid,” particularly in the context of Filipinos migrating abroad, settling there, and raising sons and daughters steeped in the culture of both native and adoptive countries. Some of these children, not quite Filipino and not quite the nationality in the country where they live, feel as a perpetual outsider, constantly prodded with issues of identity. We see this enacted in the juxtaposition of the luggage (an enduring symbol of the OFW) on which the child is astride, the sails of a ferry boat that regularly plies Victoria Harbour unfurling on her back like wings. In another painting, the same girl is beside the same luggage as the famed skyscrapers of Hong Kong loom behind her.

It’s also interesting to see how the familial, in the context of the exhibition, also defines identity. How powerful is art as a bond between the senior Habulan and his son and son-in-law? In imbibing the knowledge from senior Habulan, how do Guerrero and Geladuga address anxiety of influence in forging their own artist paths? Ama, Anak asserts that identity, once chosen, becomes destiny.

-Carlomar Arcangel Daoana