Handumanay

Lotsu Manes

September 30 to October 23, 2017

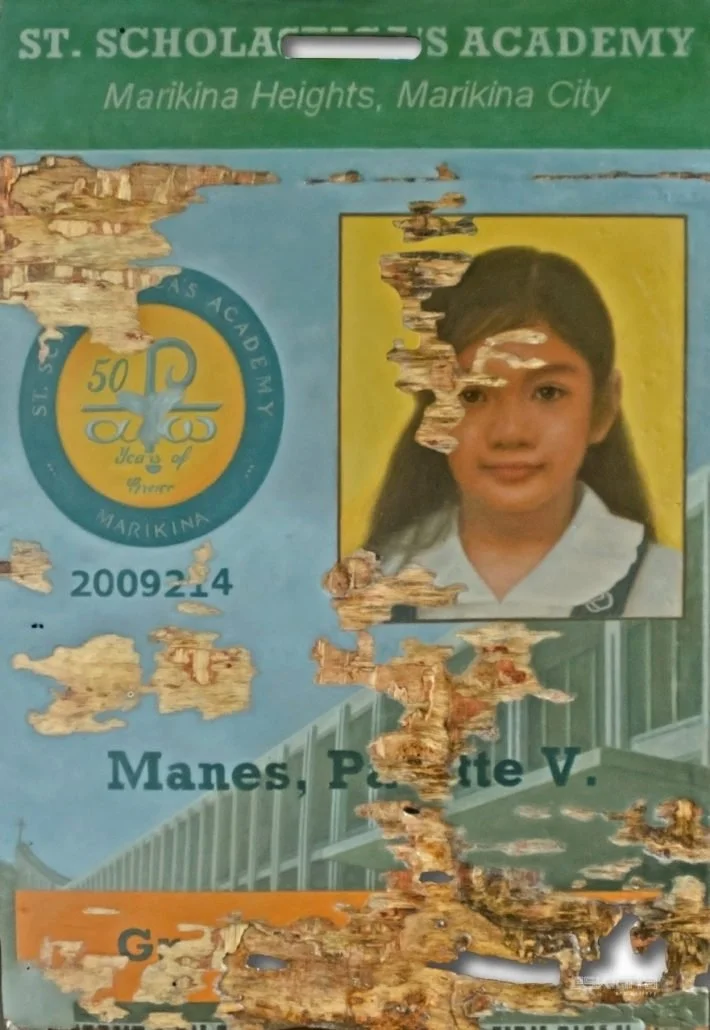

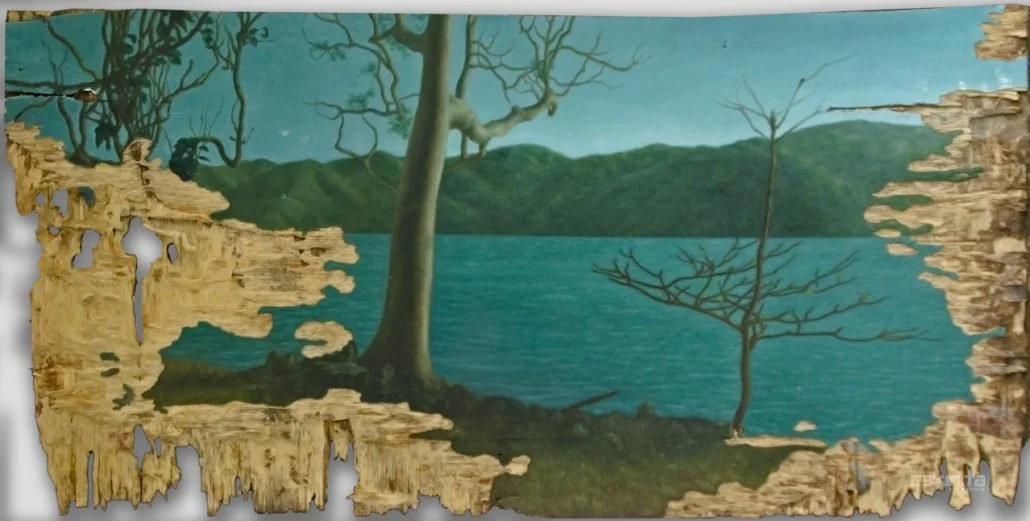

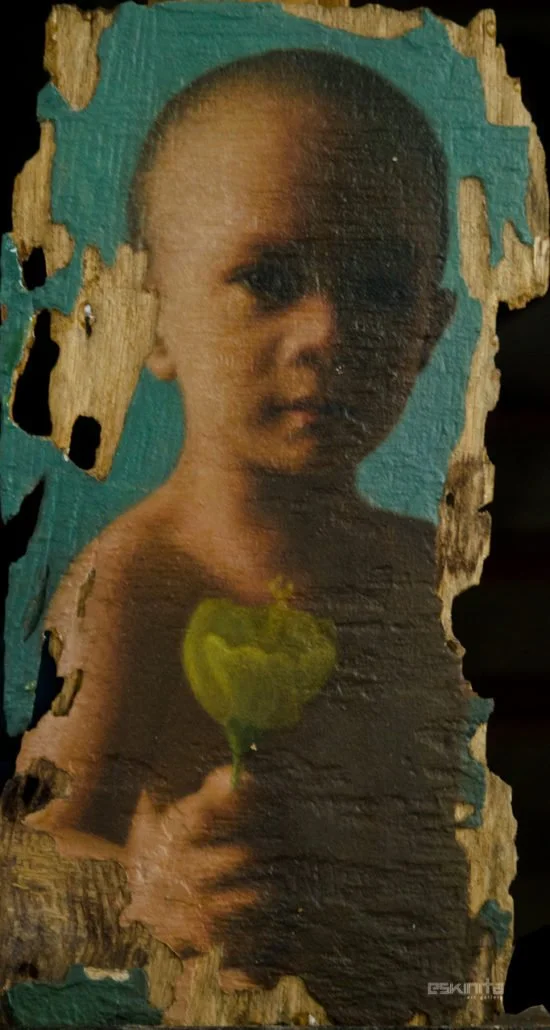

Eaten into by termites, revealing holes and areas of degradation, undoubtedly ravaged, the wooden support chosen by Lotsu Manes to define his body of work marks a radical departure from the usual choice of canvas in contemporary art—a foregrounding of the material element as predicator of content as well as an embrace of the corruption of such materiality.

When other artists induce this destruction through an actual violence of the medium (scraping, slashing, burning) or through a defacement by pigment, Manes relies on the slow but methodical process of consumption by these little ravenous insects which, among their other insidious acts, undermine structural stability of houses. After having silently chewed their way into foundations, posts and beams become no more than hollowed-out shells of their former dependable incarnations.

In Handumanay (a word from the Visayas that closely means “recollection”; note, too, of the last four letters, “anay,” that trail the word), Manes examines the erosion of memory as well as those that hold a record of it—photographs, an identification card, and a bill which, to some extent, preserves a kind of national identity. Once translated to his chosen medium, both subject and keepsake, the depicted and the record, share the same fate: their vulnerability is made evident. We as viewers look at his paintings as salvaged (denoting both “saved” as well as the vernacular connotation of “destroyed”) documents. Without these remnants, their destruction is complete.

But what is important to underscore is Manes’ artistic process: that he paints not because of, but despite, the destruction. The fact that these paintings (usually of people and places he loves) have been made suggests the artist’s valiant attempt to affix, one more time, cherished remembrances on a slate of permanence. A view of San Mateo, Rizal as well as the seaside house in Romblon he inherited from his parents are juxtaposed against encroaching, inevitable decay but, in their transformation through art, they continue to insist their presence, their here-ness.

If anything, the works of Manes are against amnesia. The depiction of an identification card of his daughter mirrors the recent spate of killings of minors because of the government’s war on drugs. The ruined places are symbolic of the wounds, bruises, and violations inflicted on their young bodies. We may have accepted that the nature of memory is prone to deterioration, but it’s more difficult to come to terms with the mortal limits of our bodies, especially those of the young, who brim with promise and hope but are felled before their time.

Handumanay then is an unflinching attempt to recall those that are sliding near their end as well as those that we wish to forget. Manes, by painting them on a ravaged support, paradoxically makes them all the more whole, urgent, unmissable. Their impending sense of mortality puts into sharp contrast the brilliant trace of their remaining life, just like a meteor fiercely bursting into flames before becoming ash. It is this light that we glimpse of each time we look at his paintings, imprinting deep in the recesses of our minds and hearts their radiant and significant fire.

–Carlomar Arcangel Daoana