Lilok

Francis Bejar/ Jerry Buccat/ Ichie Buxani/ Martin Genodepa/ Paola Germar/ Darwin Guevarra/ Jojo Lofranco/ Joshua Palisoc/ Pamela Quinto/ Jerson Samson/ Clairelynn Uy

October 28 to November 20, 2017

Sculpture—as craft, tradition, and artistic medium—can be traced back to our precolonial past, usually expressed as evocations of our homegrown gods. Now considered as ethnographic and archeological finds, these sculptures nonetheless still assert their presence, still keeping guard over one’s house in certain cultures or being prayed to for a hope of a better weather or harvest. Their contemporary translations as Catholic icons do not diminish their power. The various festivals devoted to Jesus Christ, Mother Mary, and a motley crew of saints testify to this. Even the rope that teeters to the platform where the Black Nazarene is mounted is perceived to have healing properties, the ability to shift the tides of fate and fortune.

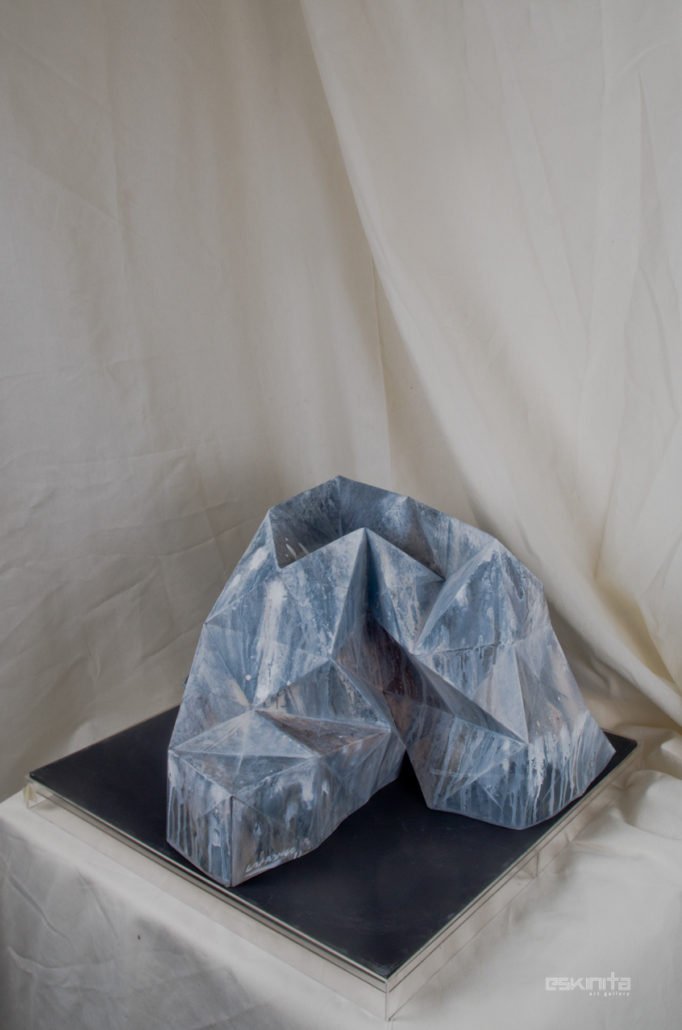

With the advent of modernism, most sculptures departed from this mode of spiritual instrumentality, from its role as a bridge to sympathetic magic. Against the backdrop of other three-dimensional art forms such as installation and performance, what then is the contemporary function of this age-old artistic medium? In Lilok, a group show devoted to exploring the relevance of sculpture within the Filipino context, we are shown that the artistic expression has not exhausted its urgency and claim on present conditions, and that their currency is perpetuated through the continued innovation of materials and techniques, the conceptual scaffolding that holds the objects in space, and the various interpretations of beauty they seek to attempt through durable forms.

Through the works of Francis Bejar, Jerry Buccat, Ichie Buxani, Martin Genodepa, Paolo Germar, Darwin Guevarra, Jojo Lofranco, Joshua Palisoc, Pamela Quinto, Jerson Samson, and Clairelynn Uy, we encounter head-on the medium of sculpture as a transformative agent by recalibrating our vision to accommodate new forms, new insights. For instance, we are given a fresh entry into the natural world with the evocation of amorphous biological creations, of multi-faceted minerals. Some foreground familiar objects, inflecting them with new meaning, such as the paper houses burned in honor of the dead. A few vivify conventional genres, such as the nude, by giving the female form a forward-moving dynamism.

Lilok affirms the resurgence of sculpture as a point of contemplation, as activator of space, as the record of the artist’s bodily engagement. It honors and continues the gains of some of the best practitioners in the field—from Isabelo Tampinco, Guillermo Tolentino, and Napoleon Abueva, to the women sculptors who became prominent of in 1980s, including Agnes Arellano, Julie Lluch, and Impy Pilapil. That some of the participating sculptors are also painters proves that the medium is an open field inviting those who wish to extend their vision into visible, tactile reality. Lilok carves new channels through which fresh, daring, and remarkable creative energy can flow.

-Carlomar Arcangel Daoana