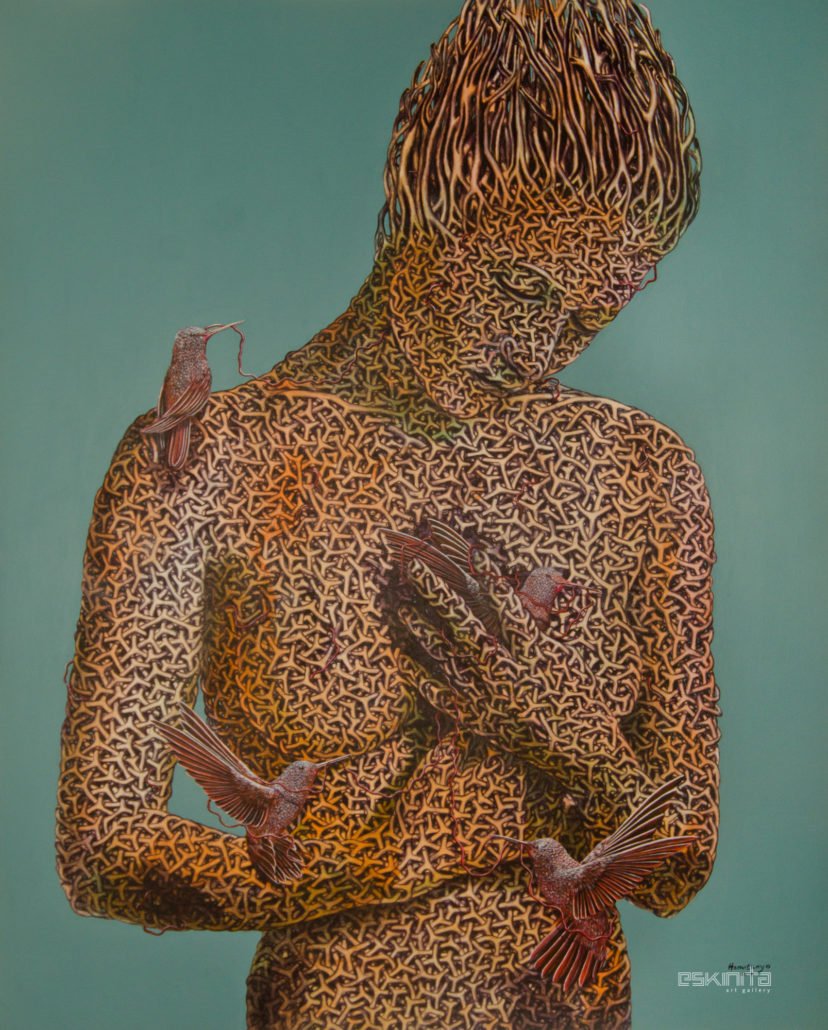

Nesting Ground

Herwin Buccat

June 2 to 19, 2018

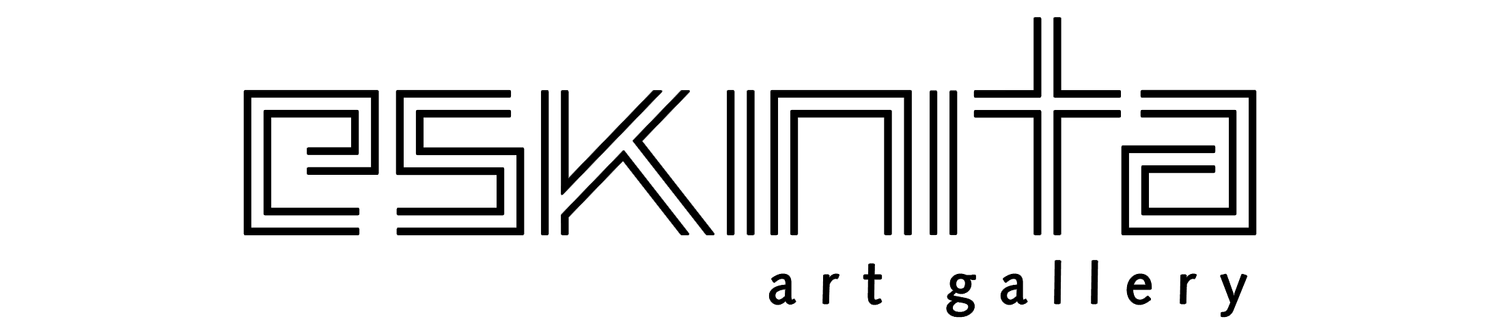

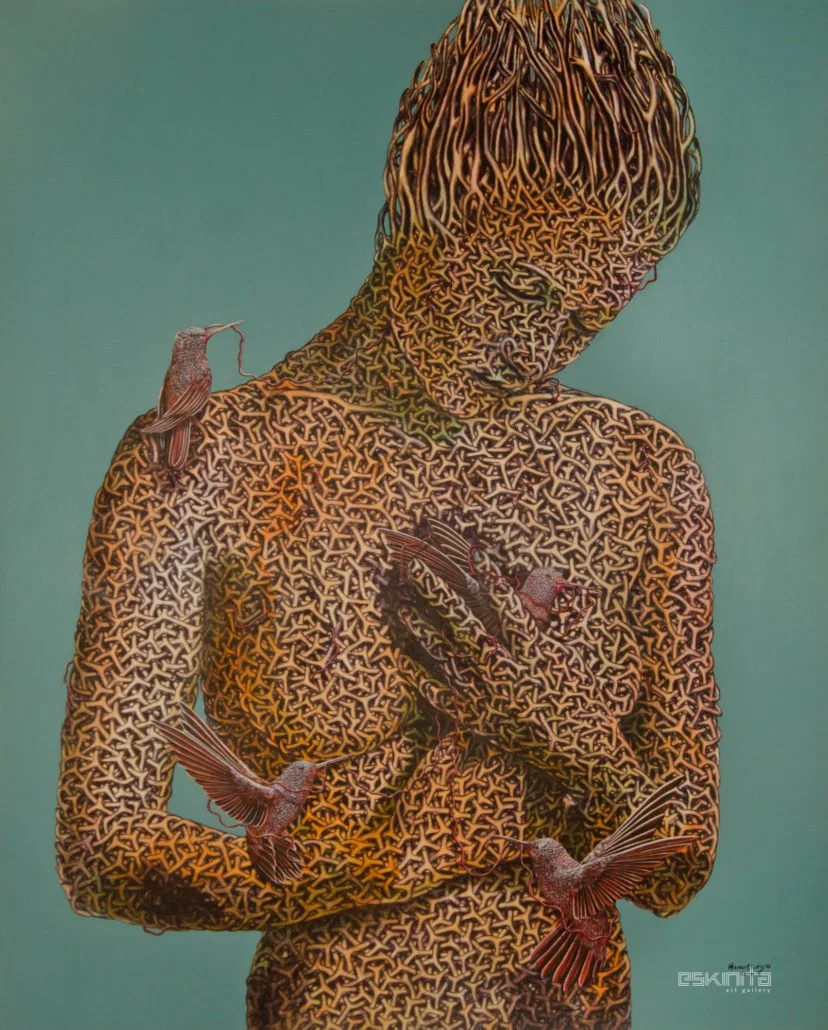

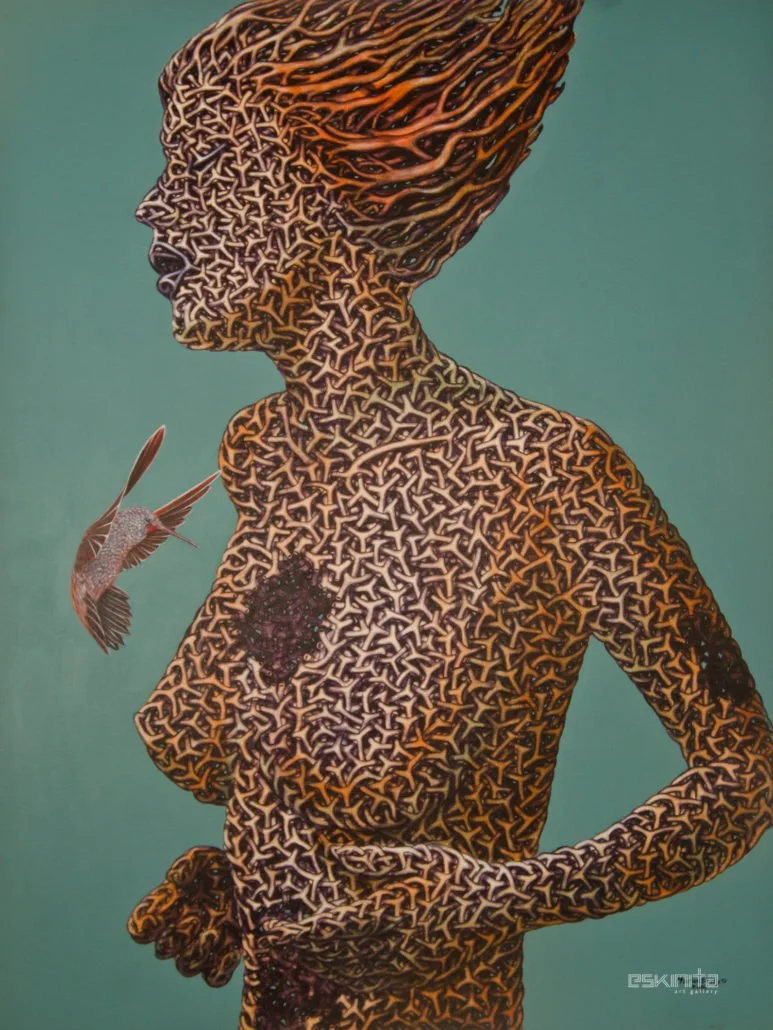

Evoked by interweaving roots to compose face and torso of a woman through intricate and meticulous technique, with no visible beginning and end, the subject matter which Herwin Buccat is known for and is in full-display in his first solo show, Nesting Ground, represents at once an allegory and archetype. This is the figure depicted variously in art history as the Cosmic Woman, the Mother Earth, the Life-Bringer, without whose ministrations life on the planet would not be possible, the eternal provider of all our vital needs.

Here she is, against a solid blue-green background, which recalls the crystalline waters of the archipelago, revealing her identity as one complete, self-sustaining root system, which gestures at the mangroves of Buccat’s beloved Bolinao. This town north of Pangasinan is the artist’s own nesting ground, a place known for its white-sand beaches and undulating landscape, still relatively untouched by bulldozing development. That the artist has chosen to anthropomorphize the natural world shows the vital relationship not only of man and nature, but of art and nature.

In his works, nature, however, is neither a background nor a receptacle of man’s pursuits—such as in the genre of landscape and seascape—but a being of quiet agency, examining the viewer through a pair of alert, piercing eyes. Sentient, unmistakably alive, mirroring us, the figure of Buccat has the power to examine our conscience with how we treat the world around us. A small tear or opening into her body means disruption of an incalculable order. In one work, she is either healing or disintegrating, which will depend largely on the action we will take late in the stage of the degradation of the planet, with the seemingly irreversible global warming and the unabated pollution of our seas, lands, and skies.

For Buccat, we might as well take our lead from the rest of creation that does its part in perpetuating the circle of life, represented by the birds that seem to draw sustenance from the figure while at the same time fixing her frayed edges. This give-and-take relationship appears to be the most rational approach to our interaction with the planet if we are to ascertain our continued survival. As the birds eat fruits, they also scatter seeds and, in the process, birth the next generation of trees. Buccat dreams of a day when each and every man and woman will plant a tree for every year of his or her life as an act of gratitude to the planet.

While not hortatory in their environmental commentary, the works of Buccat constitute a powerful evocation of our inextricable connection to the natural world. Nature is not around us but is us, permitting our life and, by extension, the manifold ways with which we choose to express it. By seeing nature as us, we assign it our aches and vulnerabilities and hopefully understand that it also shares our mortal limits. For Buccat, nature is not an inexhaustible resource we can plunder to our heart’s content but a breathing, living organism—our nesting ground.

-Carlomar Arcangel Daoana