Pag-alala sa Hinaharap

Eric Guazon

March 30 to April 23, 2019

Dialectical wordplay offers cues to the gravity and political urgency of Eric Guazon’s solo exhibition, Pag-alala sa Hinaharap (Future Recall). The exhibition title itself is a double take: the word pag-alala, a heteronym that can be interpreted to mean either the act of remembering or a sense of unease and anxiety—or both.

The potential for such a reversal of readings enriches the exhibition’s purpose and impulse which is clearly articulated by the artist himself: para tanawin ang nakaraan…[at] ang madilim na bahagi ng ating kasaysayan (to look at the past and a dark chapter of our history). For these are precarious times: where spectres of Martial Law and a return to dictatorial rule loom large and real. One should recall—but also worry deeply about—the future that our history of fascist rule has unfortunately foreshadowed.

The triptych May Mga Sugat na Bumubulong (There Are Wounds That Whisper), for instance, incorporates droppers, gauze, and paint to reference the blood shed and figures felled in the wake of Presidential Degree 1081. Here, Guazon is clear about his intent and resolve as a visual artist. The exhibition overtly represents the brutality of Martial Law, which shaped the milieu and memory of his own childhood. But it is also a quiet, personal tribute to a genealogy of political struggle dedicated to his father: an activist serving the urban poor and among the millions of Filipinos who resisted and eventually toppled the Marcos dictatorship.

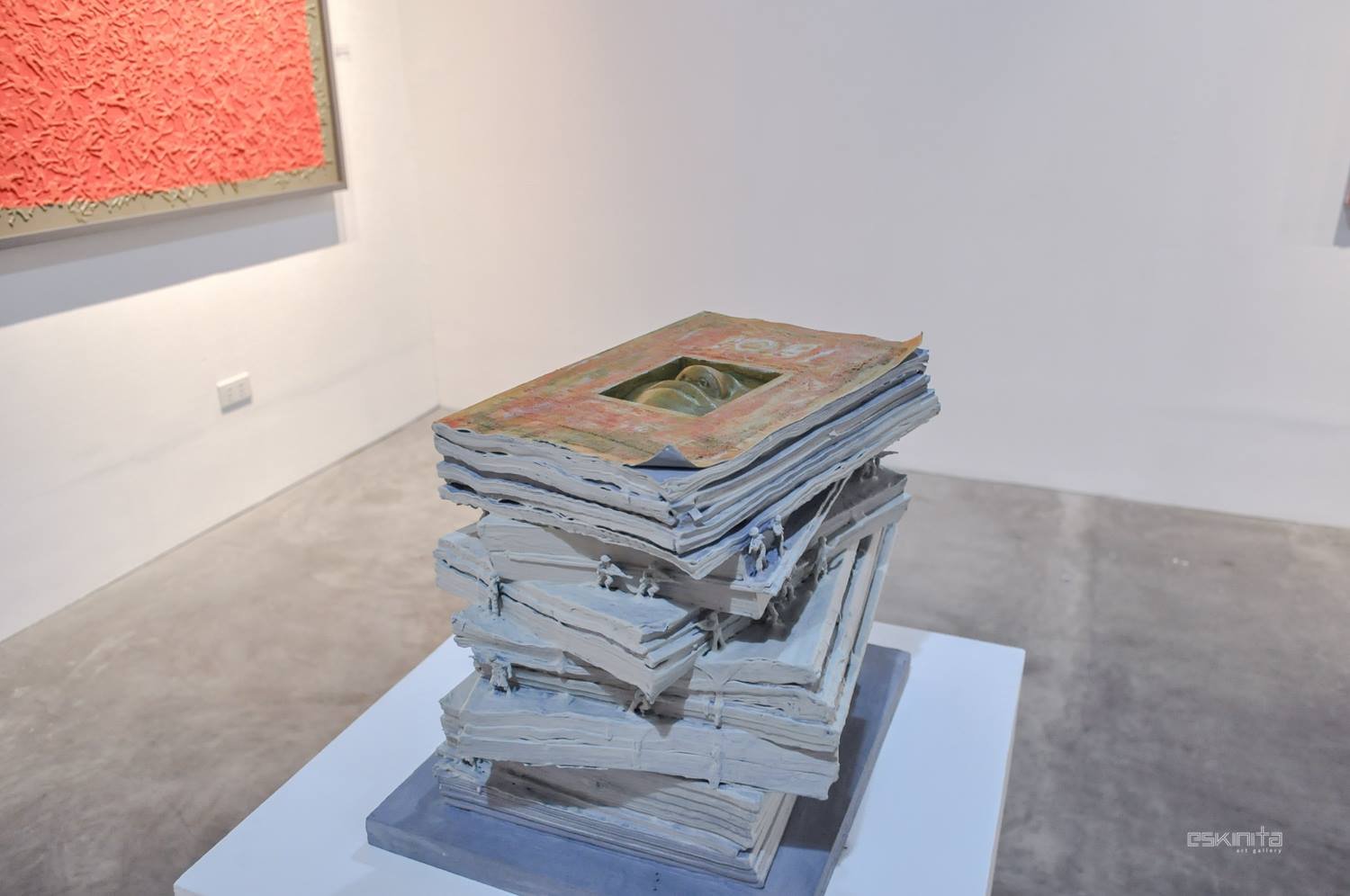

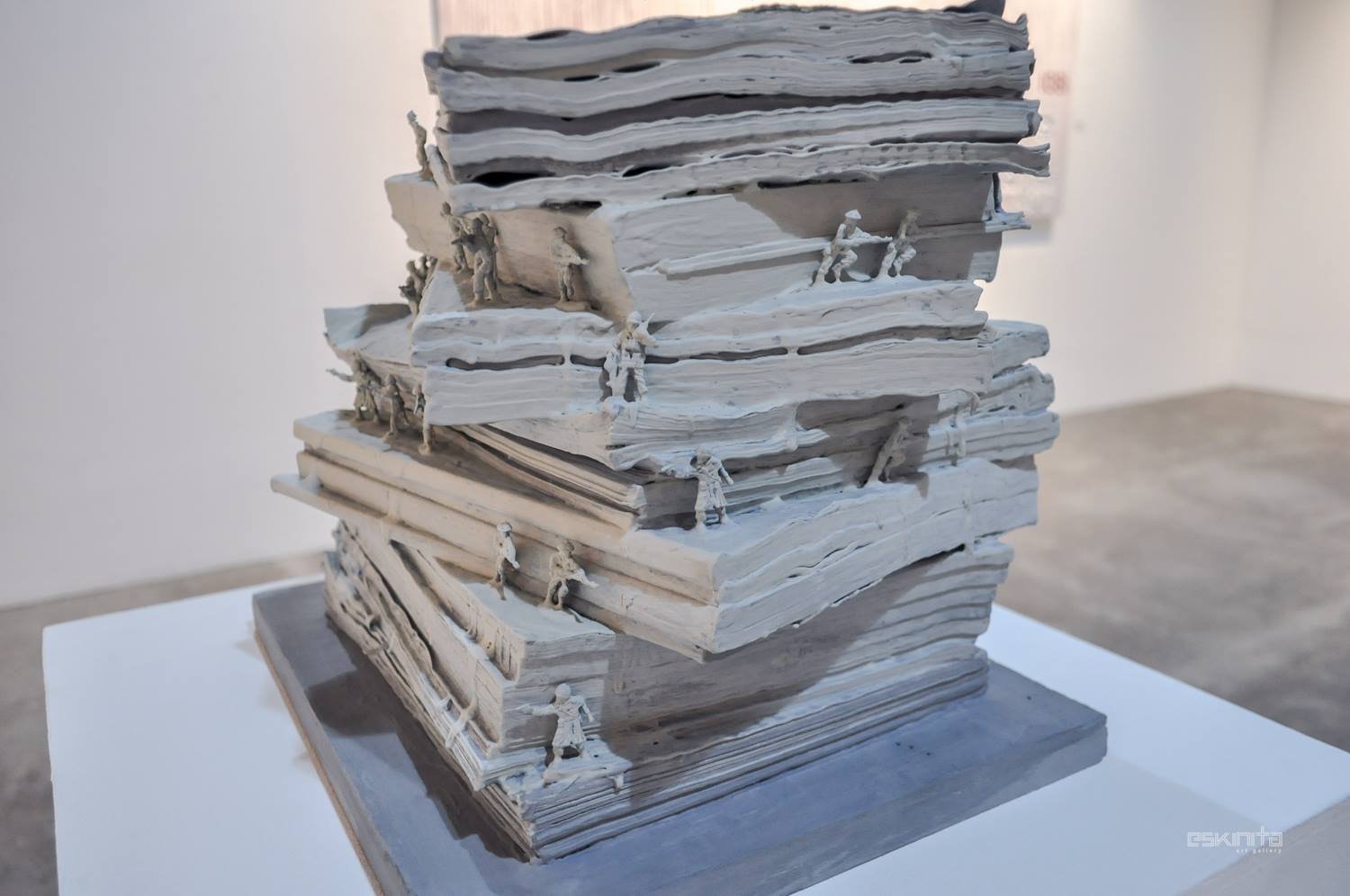

The visual complexity and layers resulting from Guazon’s distinct style, use of metaphor and symbolism, and particular choice of material is aptly demonstrated in his mixed media works. The impulse to recollect is manifested in Guazon’s choice of media. Various found objects and images, for instance, are utilized in the work Ang Bangungot ng Republika (Nightmare of the Republic) which collects various images to reference the remnants of the dictatorship: a reproduction of the iconic photograph of Marcos’ monumental concrete bust blasted open soon after the dictatorship’s downfall, a brand logo appropriating the animal symbolism of the alligator, duct tape holding intact a folded garbage bag. The installation work titled Declassified, on the other hand, implies how silence reigns even after the information on PD1081 has been publicly disclosed.

The artist is known for utilizing toy outlines and sawdust glue to create recurring patterns. Motifs and metaphors related to play, games, and childhood are visual devices explored in Guazon’s body of work, drawing out ironies and contradictions whenever juxtaposed with grimmer realities.

Guazon’s sharp commentary on the fascist past and authoritarian present, for instance, is keenly visualized and articulated in a series of three works, titled Stainless Ruler, Numbers Don’t Lie, and Camouflage. Stainless Ruler seamlessly merges the ruler as object, the reference to Pres. Marcos as a reigning ruler, and checkerboard patterns to signify how even the longest of strategized ploys eventually meet their end game and demise. Numbers Don’t Lie integrates into the composition the figure of 3257—a reference to the killings documented between the years 1975 to 1985. Finally, Camouflage overtly appropriates hues and patterns of combat uniforms with protest paraphernalia and toy figures to simulate the conduct of war games, where one must take sides or be caught in the middle. But it also references a numerical symbol—the artist and his father’s birth month—and how their lives, too, have been caught up in between these years of war.

This weighing of affinities and taking a stand brings one to the question posed by the lone lightbox work in the show: kanino ka papanig (who will you side with)? Guazon points to where he himself stands within the horizon of memory in his statement, which frames his practice as critical reflection of the past as a means to face the unease of the present: pagharap sa isang nakaraang masalimuot na kailangang intindihin at palaging alalahanin.

-Lisa Ito