Sa Panahon ng Damuho

Imelda Cajipe-Endaya/ Brenda Fajardo/ Anna Fer/ Julie Lluch

May 5 to 28, 2018

On the horizon of the art of the artists who have gathered for this exhibition is a savage. The word in Filipino, which is the title of this project, is more graphic and unerring. It is surely a reference to a political monstrosity that the artists glean in the landscape. That being said, it might be productive to delay the naming of this beast, or to leave the realization to those who must so keenly respond to the art. After all, what is presented here is a perspective through which to mediate the reality and not the reality reduced to a recognizable, easily captured icon, polemic, or prejudice.

Brenda Fajardo, Imelda Cajipe-Endaya, Anna Fer, and Julie Lluch have witnessed many monstrosities in their history and society. And their bodies of work have sensitively and diligently registered the presence of the various forces of distortion that make these monstrosities possible. At the crux of their discernment is the violence that creates conditions of excess and affliction. They sense and critique this violence and propose an ethical and therefore political position as artists. First, they make us aware of the effect and the structure that produces it. And then, they prompt us to consider a scheme through which to assess the intimate feeling and the larger context.

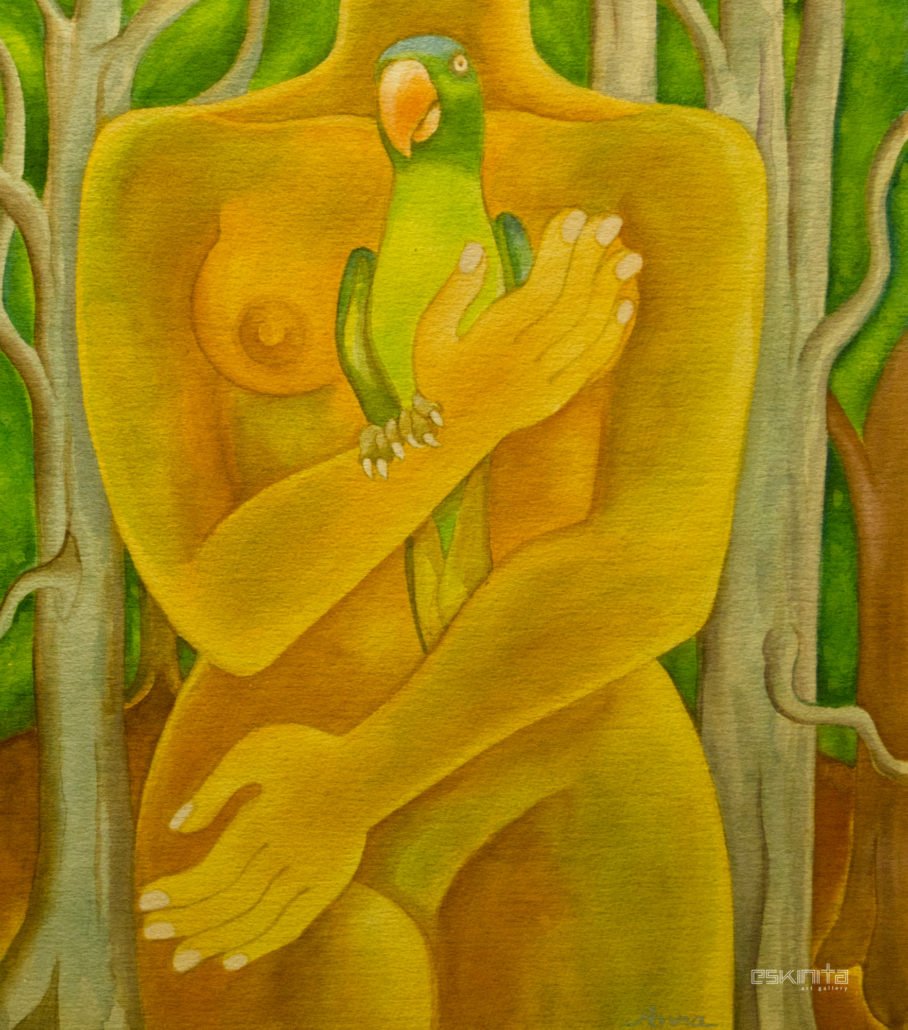

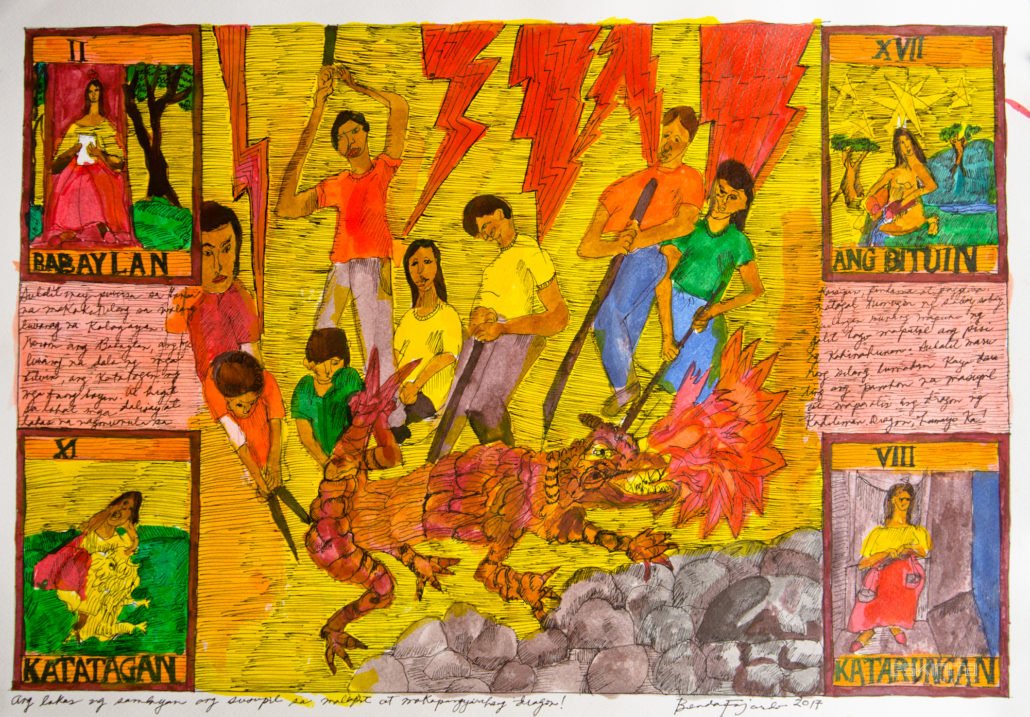

The artists trope this compelling condition in various ways, true to the aesthetic that has nurtured them across the seasons in diverse ways.

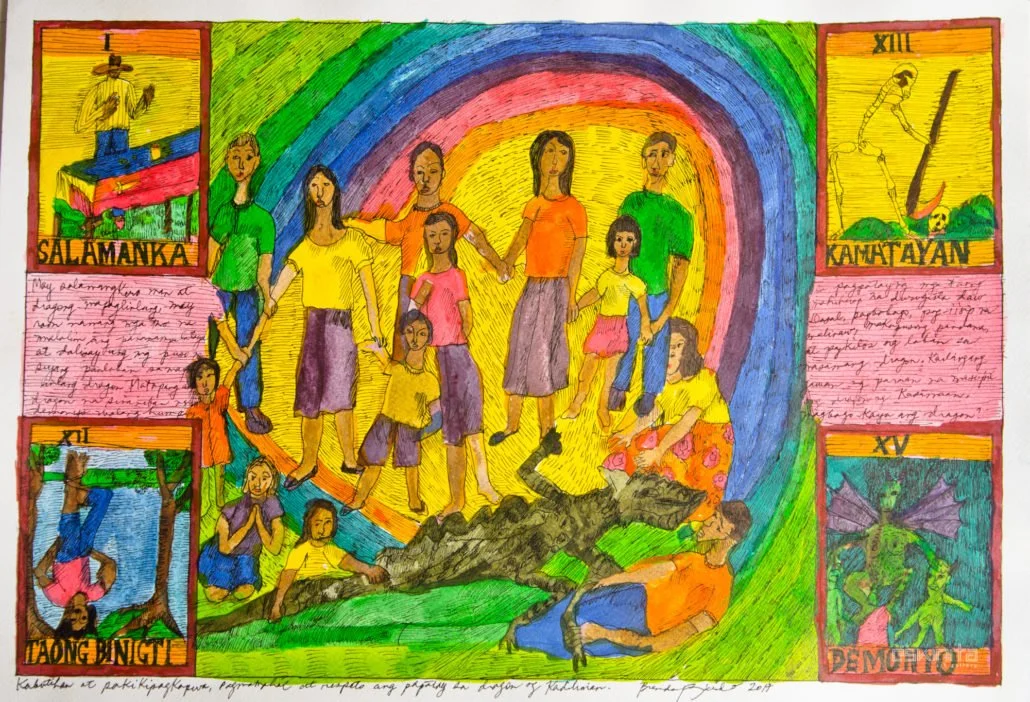

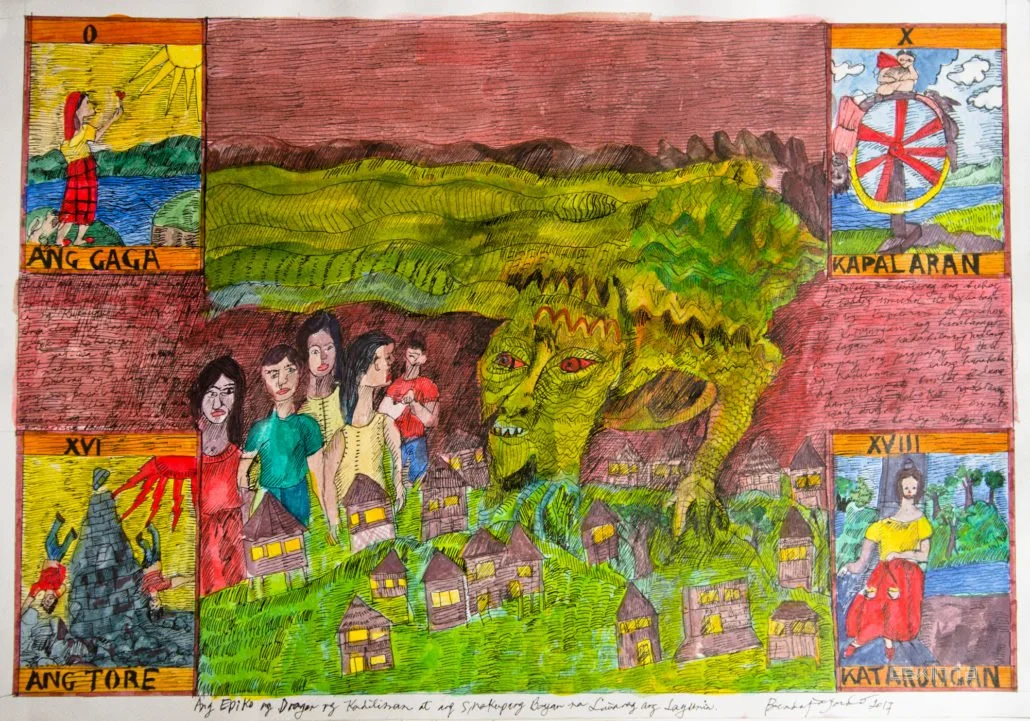

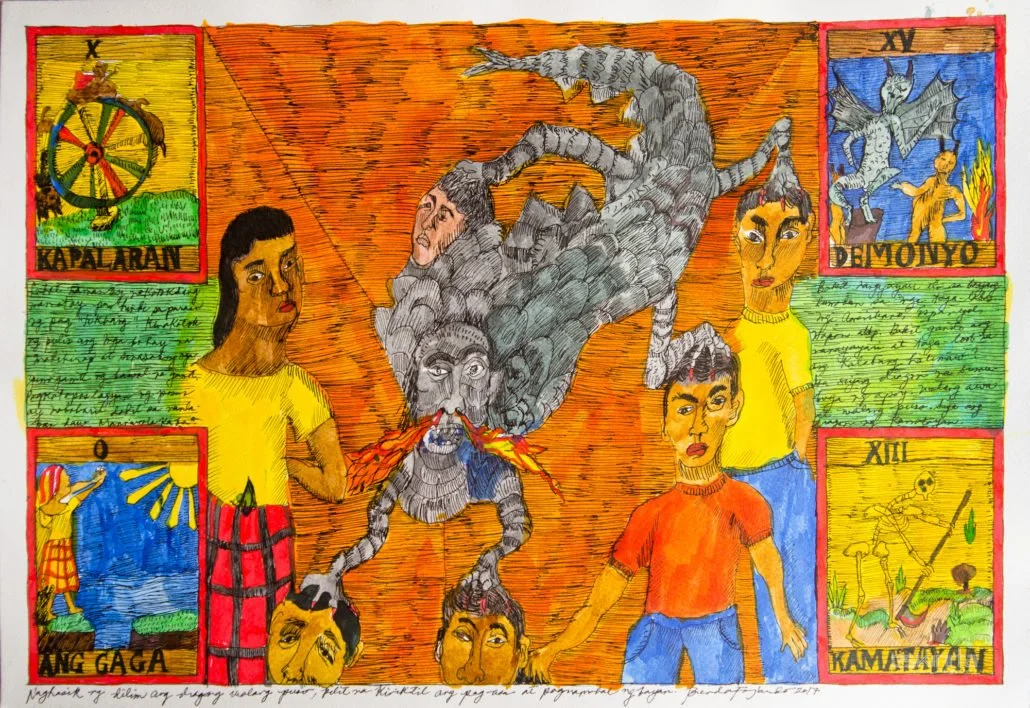

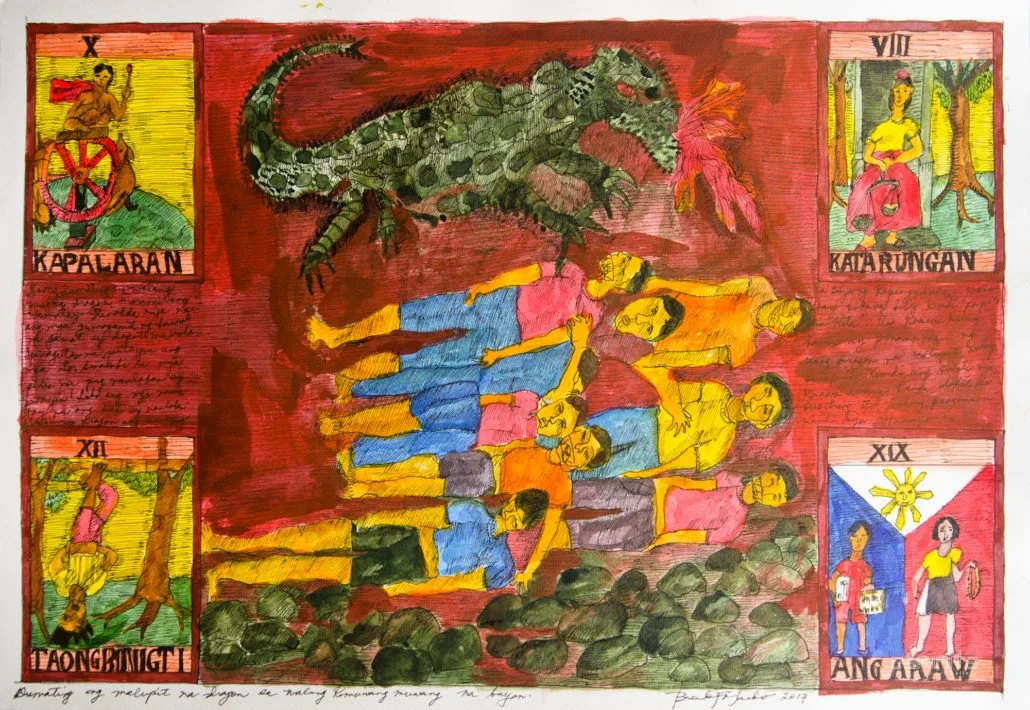

In Fajardo’s hands, it is the tarot that defines the cosmology and the fate of the savage. The central figure is the dragon that undergoes different phases of emergence and challenge from those who oppose its hegemonic stature. It is an allegorical phantom that is set up and then vanquished. This is, however, only one part of the story. Around this figure and its relationships with a community that confronts it are tarot cards bearing the characters of Medieval arcana but rendered local and therefore potent. They become salient markers of a historical unfolding, guiding the anecdote so that it may turn into an epic narrative.

For her part, Cajipe-Endaya configures a desolate scenario of exceptional perdition. It is hellish in its chromatic evocation. It is undoubtedly a scene of death, or more acutely, of fatalities, indexed by puny footprints, for instance. Like Fajardo, she tends to insinuate an apocalyptic moment. It is, in fact, a deluge as the earth has eroded and has seemingly dissolved to its core. It has become a vortex into which everything is sucked by an omniscient master, intimated only by the hegemonic eye and hand that gazes and maneuvers. In one work, there is a holy person, a saint perhaps, that carries a child through a terrain of extreme bleakness, a ruin built up by the dead. But then, there are in this saturnalia, virile bodies, too, that while may inevitably become puppets nevertheless bear the potential to resist. All this plays out on a slate of textures deriving from a variety of textile forms. The artist mixes the media of everyday clothes, curtains, and table cloths, referencing the biography and memory that are woven into them, or in fact, that weave them.

Julie Lluch turns to her paradigmatic woman figure of fired earth who is exceptionally open to the impulses of the world around her. This time she reads a list of names of people who have been executed outside of the justice system. According to her in an interview: “Spiritually…there is a fall of darkness — something sinister, like you’re being put in an evil spell. I couldn’t recognize the Filipinos anymore. They’re more vicious, they’re off. Across the land you have violence, killings, falsehoods and lies — a lot of hatred in the social media.”

Finally, Anna Fer revisits her flora, juxtaposing it with a robust woman through which the flora thrives. In one picture, the figure holds a bird close to the bosom. It internalizes a level of lyricism, a conception that is in the process of flourishing from within. But she keeps it enigmatic, hinting only at the magical realist elements of an interior terrain, a forest-woman, as it were. On the other hand, she paints a tribute to the persecuted politician Leila de Lima and what she considers her unjust incarceration and her fight against the equally grievous killings that have in her raging mind resulted in a staggering statistics of skulls.

These artists have led a solidarity of women artists since the sixties. They continue to inspire the art world and the rest of the social sphere with their lives and their artistic practice. They have also offered a range of aesthetic options to peers in terms of technique and discourses. Whether it is through rigorous drawing or expressionist sculpture, sharp storytelling or mythological sympathy, the repertoire is dynamic. Both the life of the artist and the life of the art animate a disposition to see through the world forming and deforming. Call it women’s art or feminist aesthetics. But it is also much more besides it. That being said though, without the body and the subjectivity of the woman and the artist, and the woman artist, no savage shall be crushed. In this vein, Cajipe-Endaya is the most unequivocal. From the life world of women in her art and life, she stands up against what she names “misogynist rulers.” The heart of darkness seems to be government; and in the reckoning of the four artists in this exhibition, such is the state of our times.

-Patrick D. Flores