SR

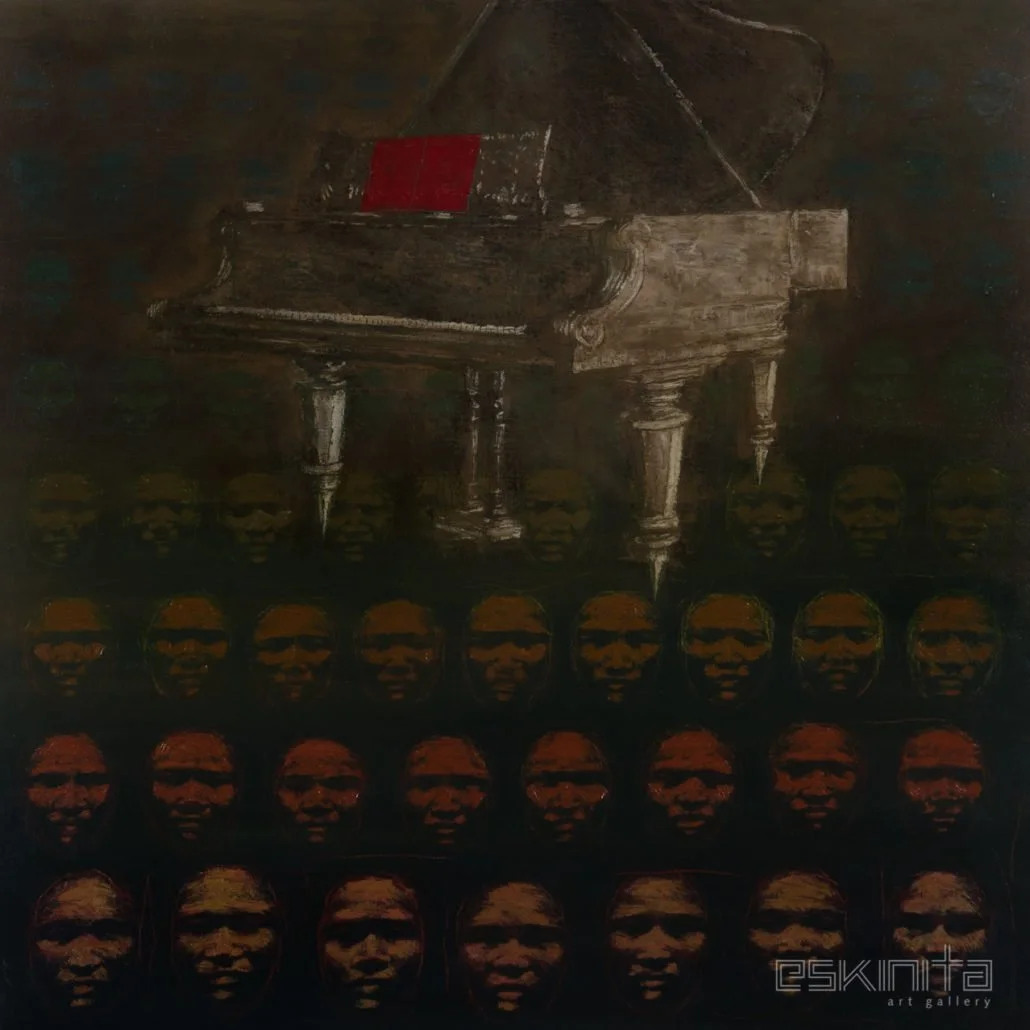

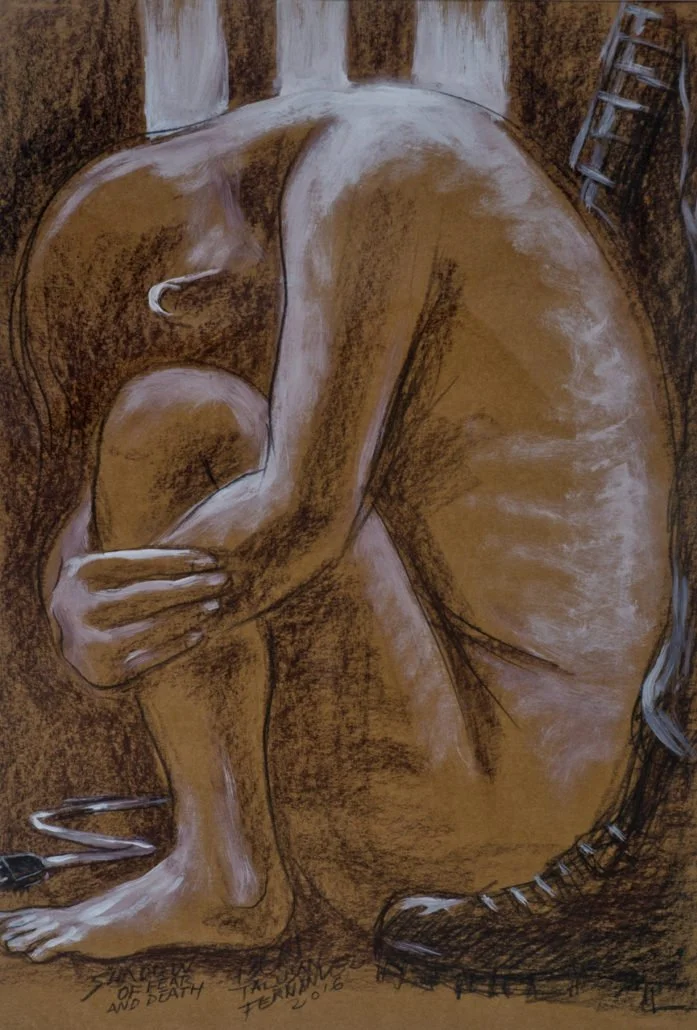

Antipas Delotavo/ Neil Doloricon/ Egai Fernandez/ Renato Habulan/ Jose Tence Ruiz/ Pablo Baen Santos

April 8 to May 10, 2017

Far from looking for the muse in scenic views, beautiful faces and fiestas, the politicized Filipino painter, during the turmoil of the First Quarter Storm, was not reacting to external conditions more fed through the eyes than being fired up by issues fed through the heart and mind. History, then, was being coursed from growing social indignation against corruption, agrarian problems, factory situations and foreign oppressions, resulting in a spate of mass of actions. Images of these were crudely captured on posters, stickers—and even on large canvas. Popular art became a compromise with urgency and broad acceptance of message. It needed not be challenging to the artistic eye. Based on elitist standards it looked like of no importance, but from a random perspective it appeared to be on a collision course with “art for art sake.”

Martial law suddenly stilled this course under a cloak of darkness and changed the scene. But was it a natural course of art history that a “new society art” would appear overnight, in place of art that depicted uncomfortable reality to the eyes of the comfortable? An art boom arose from a climate of state imposed culture, whose slogan was, “The true, the good and the beautiful.” The dictatorship found this an effective cosmetic for atrocities and all other forms of suppression. Not a few established artists became charmed by state projects like, “Kulay Diwa.” In this, an artist chose his public wall and had an outdoor painter execute the idea on it.

As martial law’s abuses corroded itself and its iron hand’s grip on civil liberties loosened from constant attacks, in various forms, both from the underground and legal organizations, here and abroad, various cultural groups became emboldened to make presentations with allegorical messages against the oppressive rule. I became one of the early politicized artists who found it an opportune time to claim a due space in a posh gallery, in 1975, to test whether political art could pass the scrutiny of critical fine tastes. Putting across a social message depicting the struggle of the broad masses, in an effective way that could reach its very subject, made it a very difficult task of uniting form and purpose. No— it can’t be achieved in my time. But hoping that the cause of the masses, through art, could stir discussions in galleries, cafes and salons, I painted for a cause in the best way I could to be an acceptable first comer in the gallery. On the streets, I joined other artists painting in forms that were fit for the streets. My first exhibit was met with both ridicule and praises: Ridicule from both artists and critics who believe that art should be autonomous and sacred, and therefore should not get mixed in politics—praises also from those who thought that it was propaganda art but, nevertheless, a welcome provocation in the local art scene.

This became my leverage in meeting up with Kaisahan, a pre-existing loose and aimless group of young artists. They were anxious of the dictatorship, for its suppression of freedom—but also excited about its sponsorship of high cultural art events at the CCP and the Metropolitan Museum, and the parallel vigour of art happenings in galleries. The first mention of politics caused many to leave the group, but curious boys stayed put and sat down to listen and talk about art and politics. Many other curious boys from outside came in.

As Kaisahan’s elected founding chair, it became my responsibility to lead the group in a discussion about the real state of Philippine Art and where it should go. In spite of the many attempts to attain national identity in Philippine Art based on traditions, ethnic past and history, the deeper reality about contemporary relationships and interactions of social classes almost remained untapped. In the group’s discussions the plight of the basic Filipino came to the fore of being at the center of our search for national identity—their oppressed situation, their struggles and dreams. It was even foreseen as a more strategic objective than the overthrow of an oppressive Marcos’ rule, affecting the civil liberties of, even, elements from the oppressor class. An assertive national identity in art could promote national unity and awareness of oppressive foreign influences. That would well be the most important contribution of the artist to nation building. This led to the writing of our manifesto, signed by all and presented at the opening of Kaisahan’s first exhibit on Dec. 6, 1976, at the Ayala Museum.

Equipped with an orientation and a detailed manual in pursuing it, the group was seen at various fronts confidently putting up more shows, conducting workshops with labor and peasant groups, standing up at school and national forums, living with ethnic groups and doing collaborative works with literary and theater groups. It was never premeditated in the process of our organizing to call our art “social realism,” but art critics did. Our art grew into a movement that spilled out of Kaisahan. Its principles stated in a manifesto gave social realism the potentiality to move from generation to generation. A broad coalition of anti-Marcos forces, that included elements from the oligarchy, big capitalist and landlords allowed crossovers between inherently opposing social classes for the sake of alliance work against Martial Law. Social realism gave us the feeling that the movement was being widely accepted in the mainstream.

When Marcos was overthrown, there surfaced an outright dichotomy between those who had a long term goal and those who had a short term goal. Not a few were quick to sentence the social realist movement to death. For some media people we ceased to be hot material. Social realism in the Philippines was born in a climate of heightened contradiction between dictatorship and civil libertarians. The sudden resolution of this contradiction created a vacuum that was temporarily disorienting to the social realists. The fall of the Berlin Wall came just three years later—then the Soviet Union, from which social realism originated, two years later. But it was not like an umbilical chord was cut too soon, for social realism in the Philippines had acquired an independent life of its own. Even among its practitioners time was good for self assessment that included internal contradictions plaguing the underground movement. The validity of the Kaisahan Manifesto still appeared to be durably valid but must be taken in light of the changing collective experience of the Filipino.

No society ever runs out of social conflicts: the very driver that ensures life for social realism. What could kill it is general artists’ apathy for the concern of others, which is remote from the humane nature of artistic sensibility. It has become a matter of identifying new conflicts or the new dimensions in which classic conflicts have morphed into. Social realist temperaments have diversified from very predictable social class anger to whimsical mockery of the social villain.

The younger SRs, including millenials are proving their mettle in coping with art that is laden with social responsibility. It’s interesting that a young and playful mind lightens art that tends to carry a whole nation or a whole world. Notably, not far off, is a number of seasoned SRs who can play around and carry on with never-aging imagination. One has learned the clever play of making art transcend a disturbing reality on canvas, making his SR painting fit to live with at home. New technology results in new form—seen on another senior SR’s use of computer savvy to create monumental, digital socio-realistic art. Some have gone as far as changing the way of looking at same old classic problems from the purely scientific way to putting spiritual way above it. One has mastered the use of folk religious images as a powerful tool to make social statements. Another has situated social realities in the broader context of scriptural realities, while staying away from traditional religious images—an approach which may be leaning on Christian Social Realism.

The current state of Philippine art is such, that there is no well defined movement that is stirring up like it did in the 70s, which drew in all other art disciplines—not apart, but in fact—born of a widespread national revolutionary sentiment. But it is also hard to ignore young talents’ coming up with new exciting forms aided by a wealth of computer tools and rush of cyber information and images. Some artists have reverted to the classic human-interest portrayal of familiar urban characters, with innovative tact, labelled by a respectable art critic as “social theme.” All these pieces are too beautiful to ignore while some of them are putting Philippine art in the world map. It makes us hear back to the conscience of the 70s: “Beautiful but for what and for whom?”

—Pablo Baen Santos